Day 08

Welcome to this year’s “you have to guess that the input is special” challenge!

Here is the code:

import Data.List

import Data.Map (Map, (!), fromList, keys)

import Text.Regex.TDFA

import System.Environment

data Node = Node { left :: String, right :: String } deriving (Show)

type Input = (String, Map String Node)

type Output = Int

parseInput :: String -> Input

parseInput = (\(inst : _ : nodes) -> (cycle inst, fromList . map getNode $ nodes)) . lines

where getNode node = (\[idx, l, r] -> (idx, Node l r)) $ tail . head $ (node =~ "(.{3}) = .(.{3}), (.{3})." :: [[String]])

partOne :: Input -> Output

partOne (input, network) = length . takeWhile (/= "ZZZ") . scanl next "AAA" $ input

where next curr 'R' = right $ network ! curr

next curr 'L' = left $ network ! curr

partTwo :: Input -> Output

partTwo (input, network) = foldl1 lcm $ map getLength starting

where starting = filter ("A" `isSuffixOf`) $ keys network

getLength start = length . takeWhile (not . ("Z" `isSuffixOf`)) . scanl next start $ input

next curr 'R' = right $ network ! curr

next curr 'L' = left $ network ! curr

Let’s go quick here, let’s talk about the input:

data Node = Node { left :: String, right :: String } deriving (Show)

type Input = (String, Map String Node)

type Output = Int

parseInput :: String -> Input

parseInput = (\(inst : _ : nodes) -> (cycle inst, fromList . map getNode $ nodes)) . lines

where getNode node = (\[idx, l, r] -> (idx, Node l r)) $ tail . head $ (node =~ "(.{3}) = .(.{3}), (.{3})." :: [[String]])

I have a data structure Node that represents the successors of a Node in my graph. My input is a pair containing a String (my instructions) and a Mapping from String to Nodes that represents my graph (the key is the node’s id and the value is its successors).

To parse the input, I first start by splitting by lines. The first line is my list of instructions, that I tranform into an infinite cycle (as instructions are cyclic). I skip the second (empty) line.

For each line starting at the third line, I get the node represented by that line with a regex (because why not), and I create my mapping from the data I retrieve from the regex.

Part one is pretty easy:

partOne :: Input -> Output

partOne (input, network) = length . takeWhile (/= "ZZZ") . scanl next "AAA" $ input

where next curr 'R' = right $ network ! curr

next curr 'L' = left $ network ! curr

Simply put: I start at node “AAA”, and I follow the instruction until I am on node “ZZZ”. I keep each step inside a list, and when I’m on node “ZZZ” I look at the length of my list: this is my answer AKA the number of steps I took.

To know which path I should took at a specific step, I look at the current instruction: if it is ‘R’ (resp ‘L’) then I select the right (resp left) path from my current node in my graph (which I called network).

Part two is pretty similar:

partTwo :: Input -> Output

partTwo (input, network) = foldl1 lcm $ map getLength starting

where starting = filter ("A" `isSuffixOf`) $ keys network

getLength start = length . takeWhile (not . ("Z" `isSuffixOf`)) . scanl next start $ input

next curr 'R' = right $ network ! curr

next curr 'L' = left $ network ! curr

The getLength function does exactlty the same thing as partOne, except I stop when my node ends in “Z” instead of when it is “ZZZ”. I launch that getLength for each node ending in “A”, which I get by filtering on the keys of my network/graph.

The annoying thing about that puzzle, and the reason why I am doing exactly the same thing as part one for now is that the input is made in such a way that: for each starting “A” there is only one ending “Z”. Following the path after this ending “Z” will led back to the same “Z” in exactly the same amount of step: i.e we are dealing with a bunch of fixed length cycles.

When you want to find the minimal number of elements needed for cycles to end at the same time, you simply take the least common multiple of these lengths:

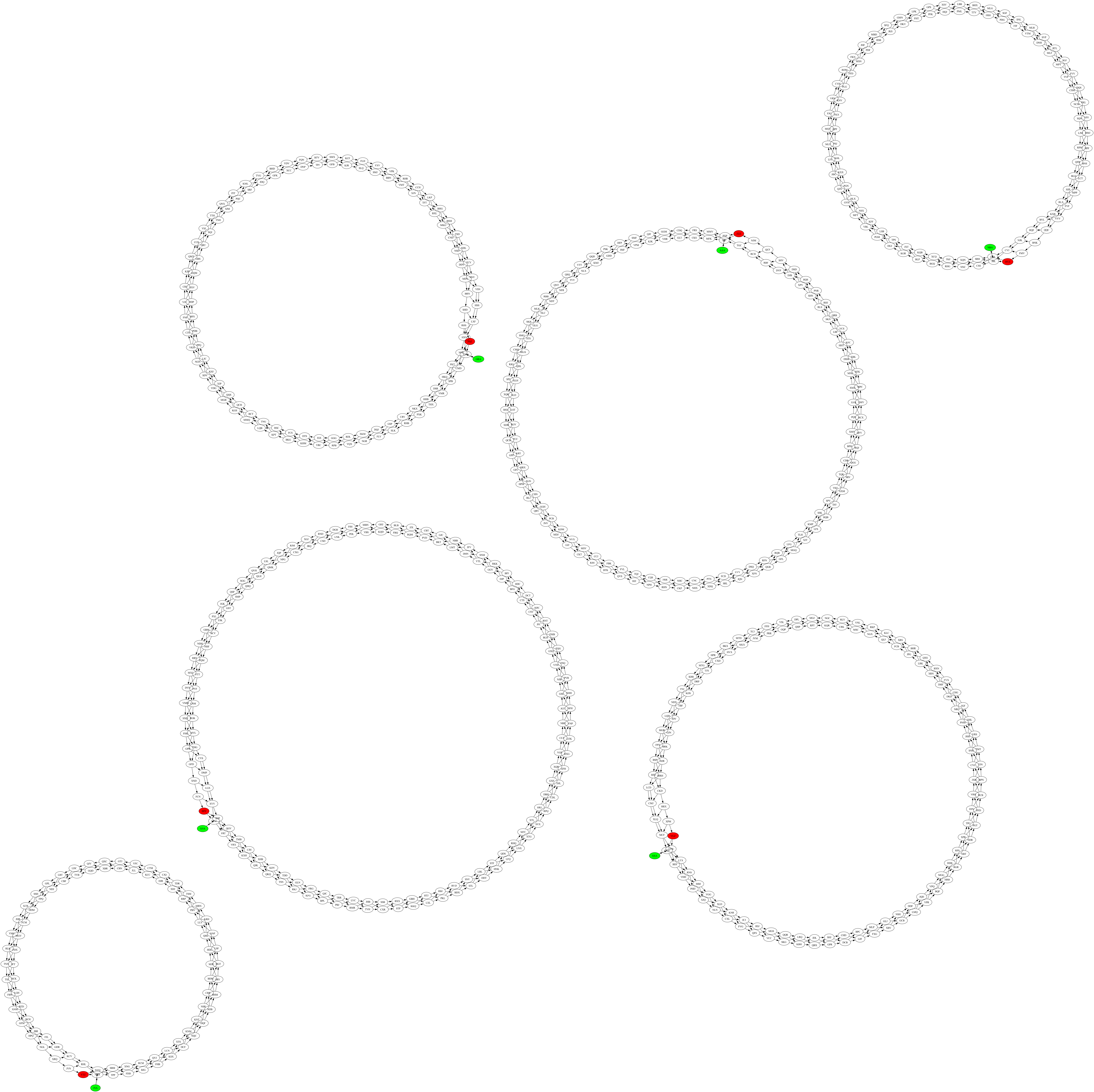

I think it is easy to see why this is related to the LCM with a visualisation:

Let’s say you have two cycles, one of length 3 (which I will represent with 012) and one of length 4 (which I will represent with 0123). My goal here is to find a moment where they will both end at the same time. To do so I can keep writing both cycles at the same time until this happens:

012301230123 012012012012

Here for example I found out that they stop after 12 elements. Notice one interesting thing about how we worked here:

Because we want to find a place where both cycles ends, we always end up writing entire cycles.

This means that the number of elements on the first line is a multiple of 4 (the length of the first cycle), otherwise it would mean that we would have not ended the line at the end of the cycle

This also means that the number of elements on the second line is a multiple of 3, for the same reason

This tells us that the number of elements needed for both cycles to end at the same time is always going to be a multiple of both cycle length.

Now you can test this out: try another multiple of both 3 and 4 (let’s call it n), write the first line with n elements in it, do the same with the second line, and you’ll notice that they end exactly at the same time!

Now we know that to find a number of elements needed for both cycles to end at the same time, we simply need to find a number that is a multiple of both cycles: that is a common multiple.

To find the minimum number of elements, we therefore need to find the smallest common multiple of both cycle lengths: AKA the least common multiple

Now the great question is: how do I know that the input makes cycles? The fun thing is: I didn’t. I simply had a gut feeling that it would.

However, it is interesting here to get a graphical representation of my input graph!

I have provided a small shell script to generate your own!